Writing in books

This is not a typical blog post, but it is certainly too long to be a social media post! I started thinking about people writing in books, and these are my musings on the topic.

It started when I saw a post by Jenny Lawson, a local writer and independent book shop owner, in which she talked about some books she had purchased from the late Shelley Duvall’s estate.

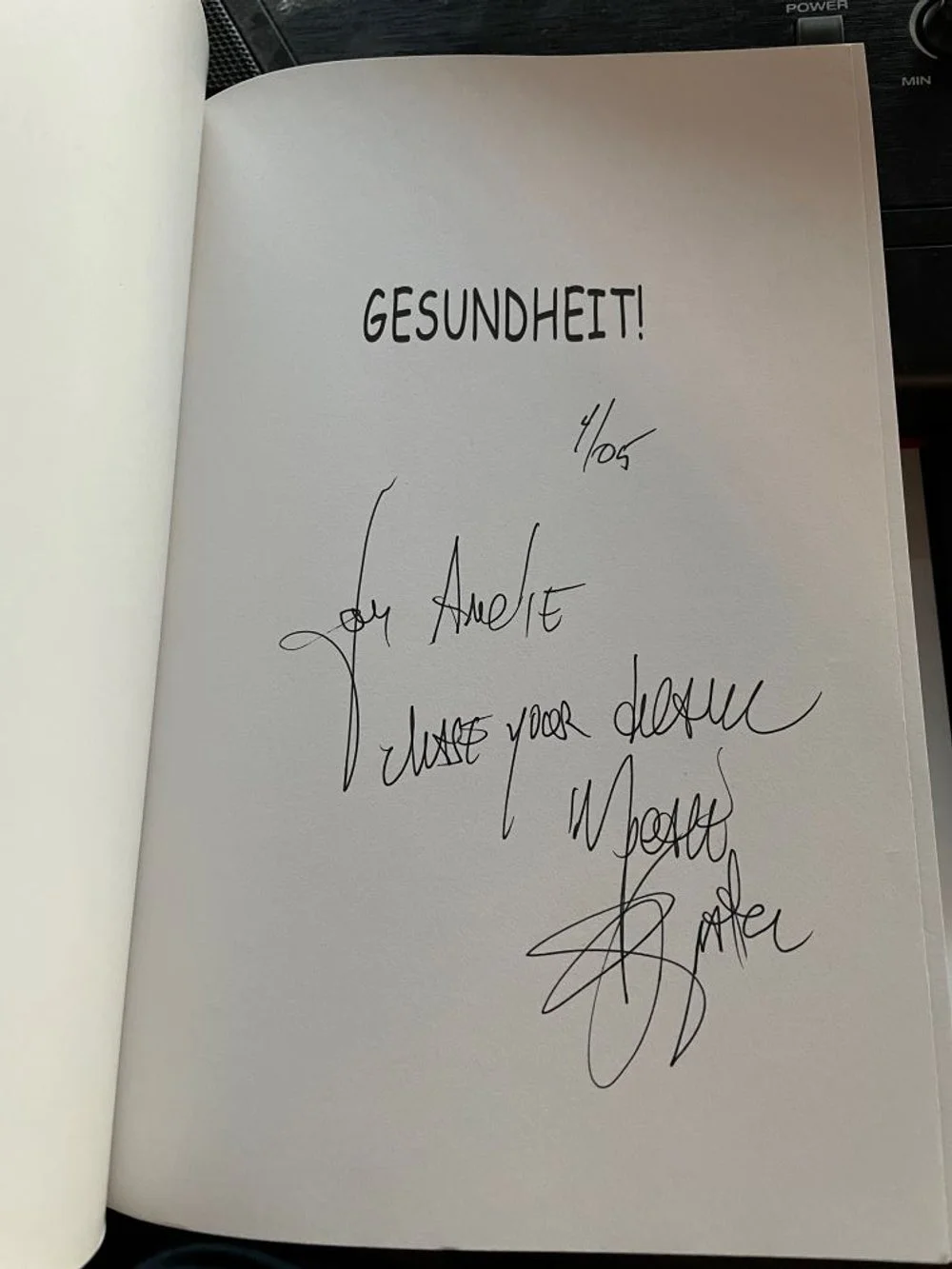

Picture from Jenny Lawson’s Instagram feed, @thebloggess

When she acquired a book, Shelley Duvall had the habit of writing her name, the date, and the city in which she was at the time. In her case, it increased the value of the book because she is famous. (Jenny Lawson is now contemplating doing the same thing, and she is famous enough that there would be a market for it.)

This got me thinking… When is writing in a book okay, and when does it take away from the value of the book? I personally never write in my books; when I make a modification to a recipe, for example, I write my comments on a sticky note and put that on the page, instead of writing directly in the book. When I buy a used book, I certainly prefer it if it hasn’t been marked up. Used children’s books bearing a gift inscription on the inside cover page always make me sad. So, us non-famous folks should just refrain from ever marking up the pages, right?

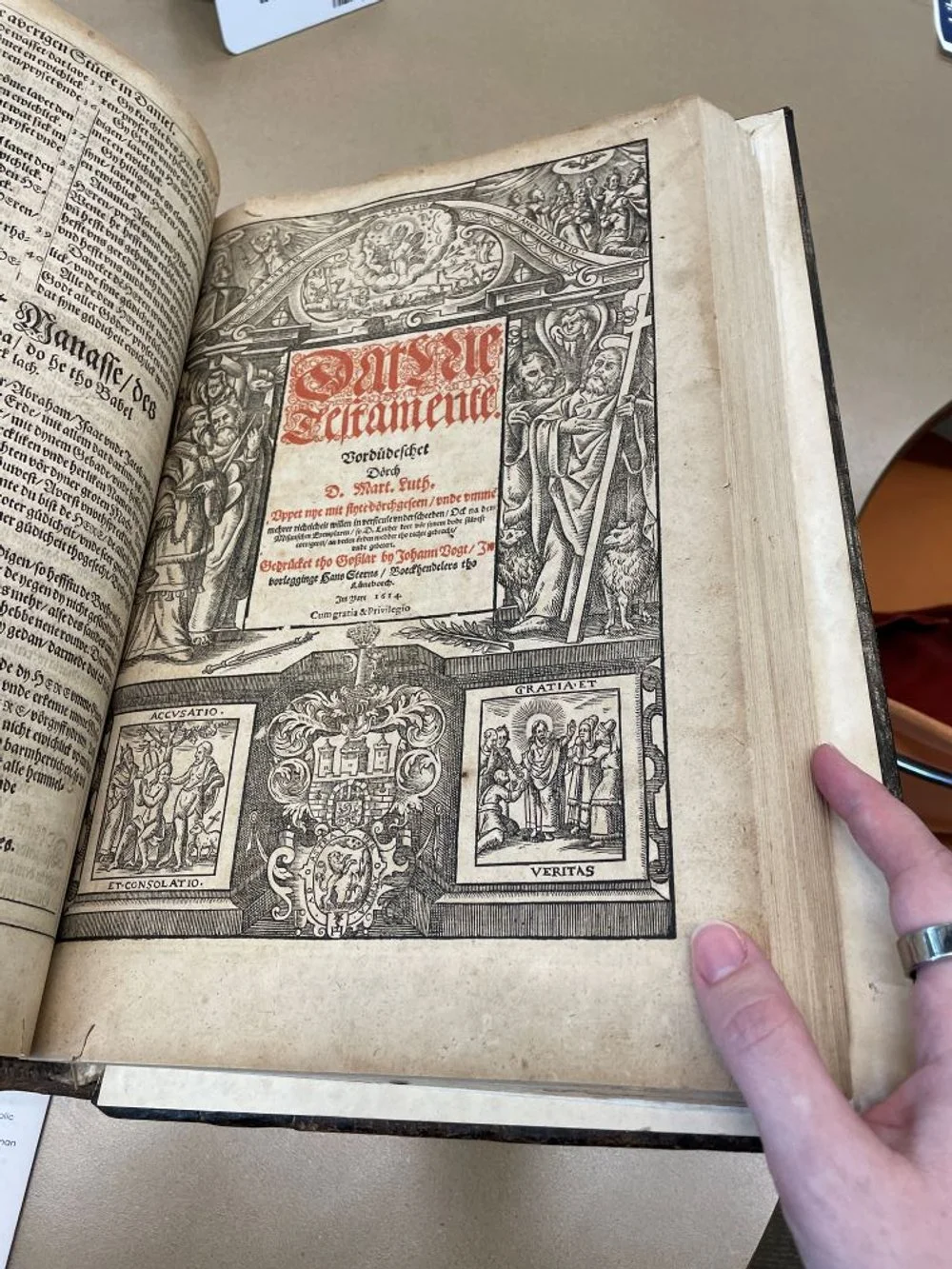

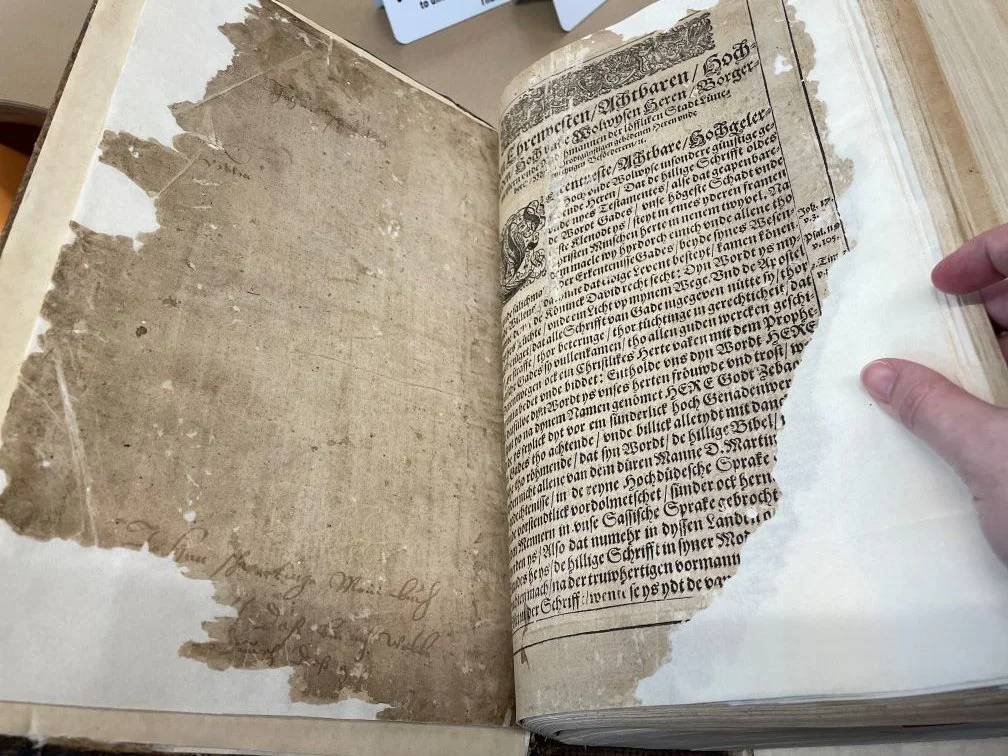

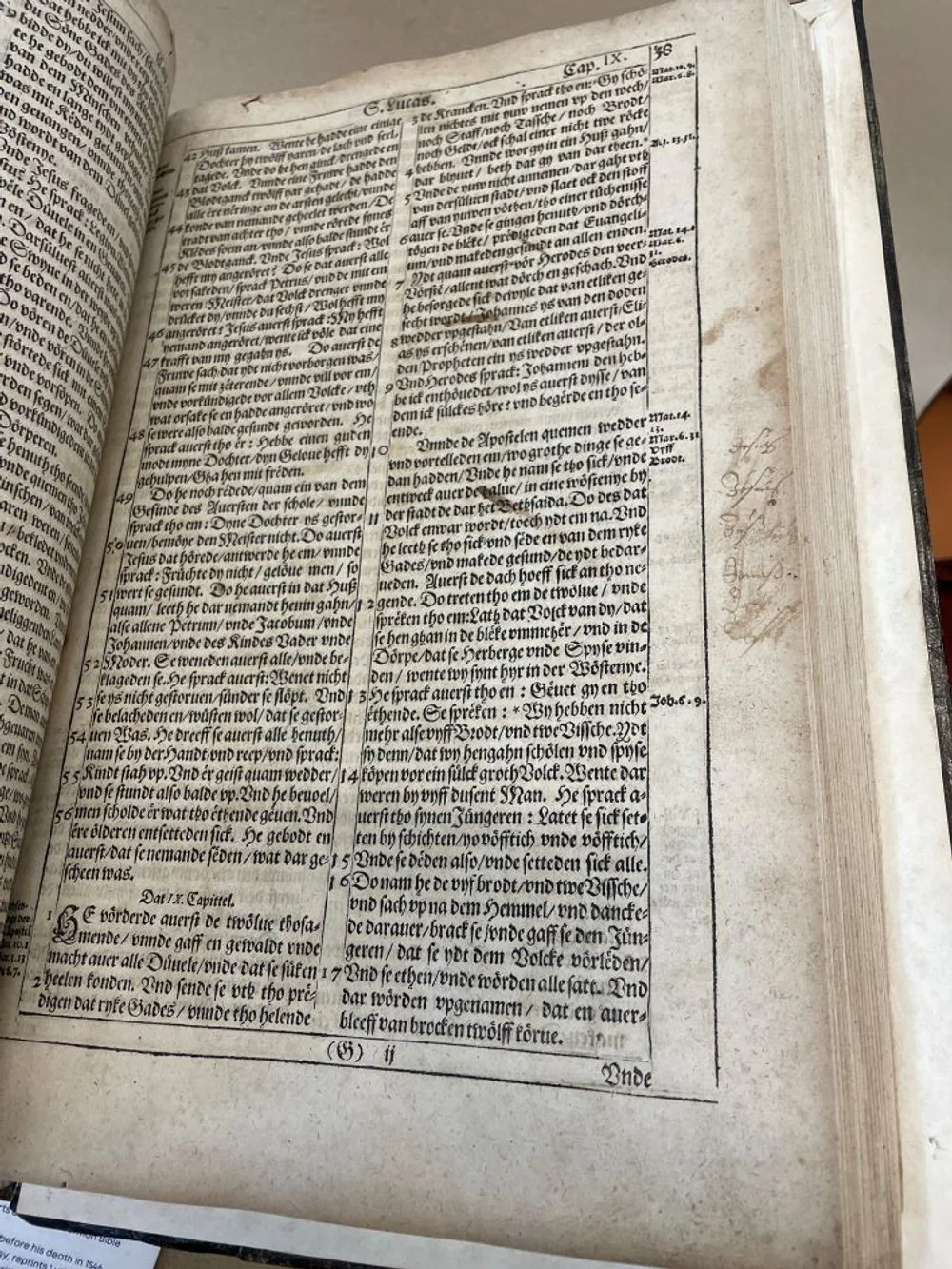

A few days after that, something else happened that changed my mind about it. I went to see the Low German Bible from 1614 and noticed that it was marked in some spots. The most notable is the name of one of the owners, Johan Schwarting, written on the inside cover along with the inscription “my book” in German. He acquired this Bible when it was already over 200 years old. A few other pages inside the Bible have notes that someone scribbled in the margin. And at this point, centuries down the line, I think that those hand-written notes automatically make the book more interesting, because it’s like a time capsule that makes us think about people who lived so long before we did.

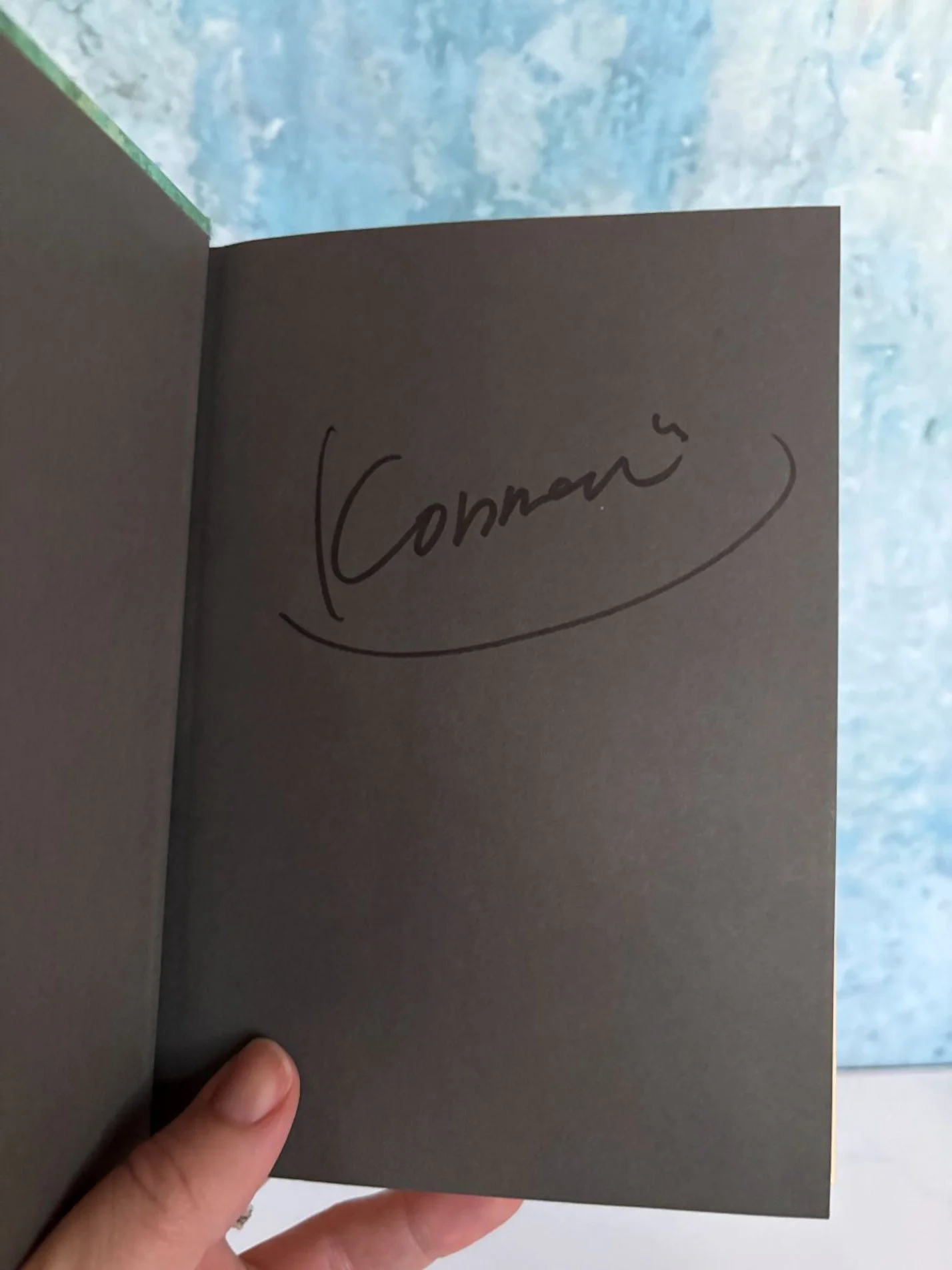

There are some types of markings that we all agree are good. Like when a book is signed by the author, that automatically makes it better, right?

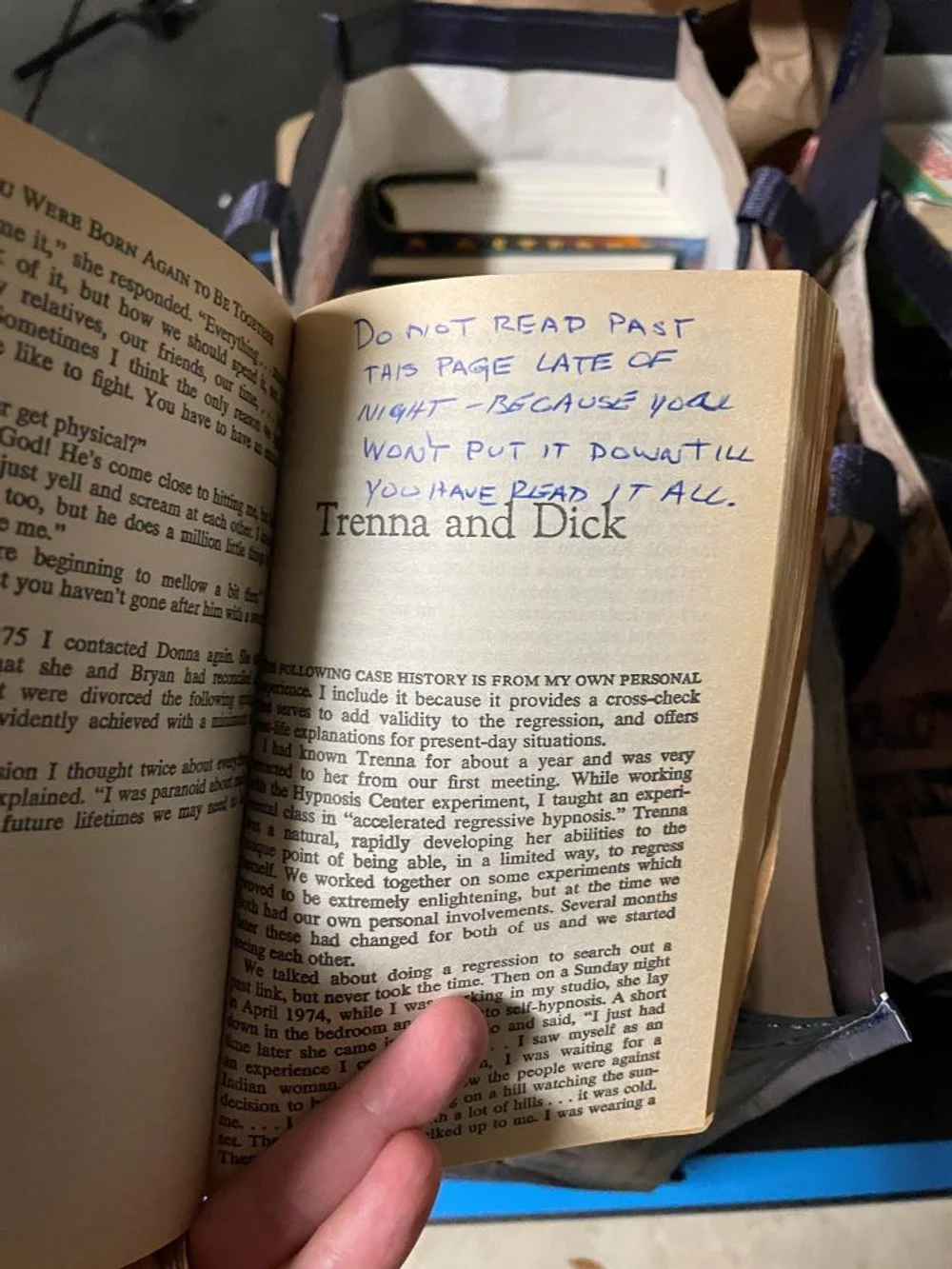

Does it make a difference if the note was meant strictly for the person who wrote it versus meant for whomever might read it later?

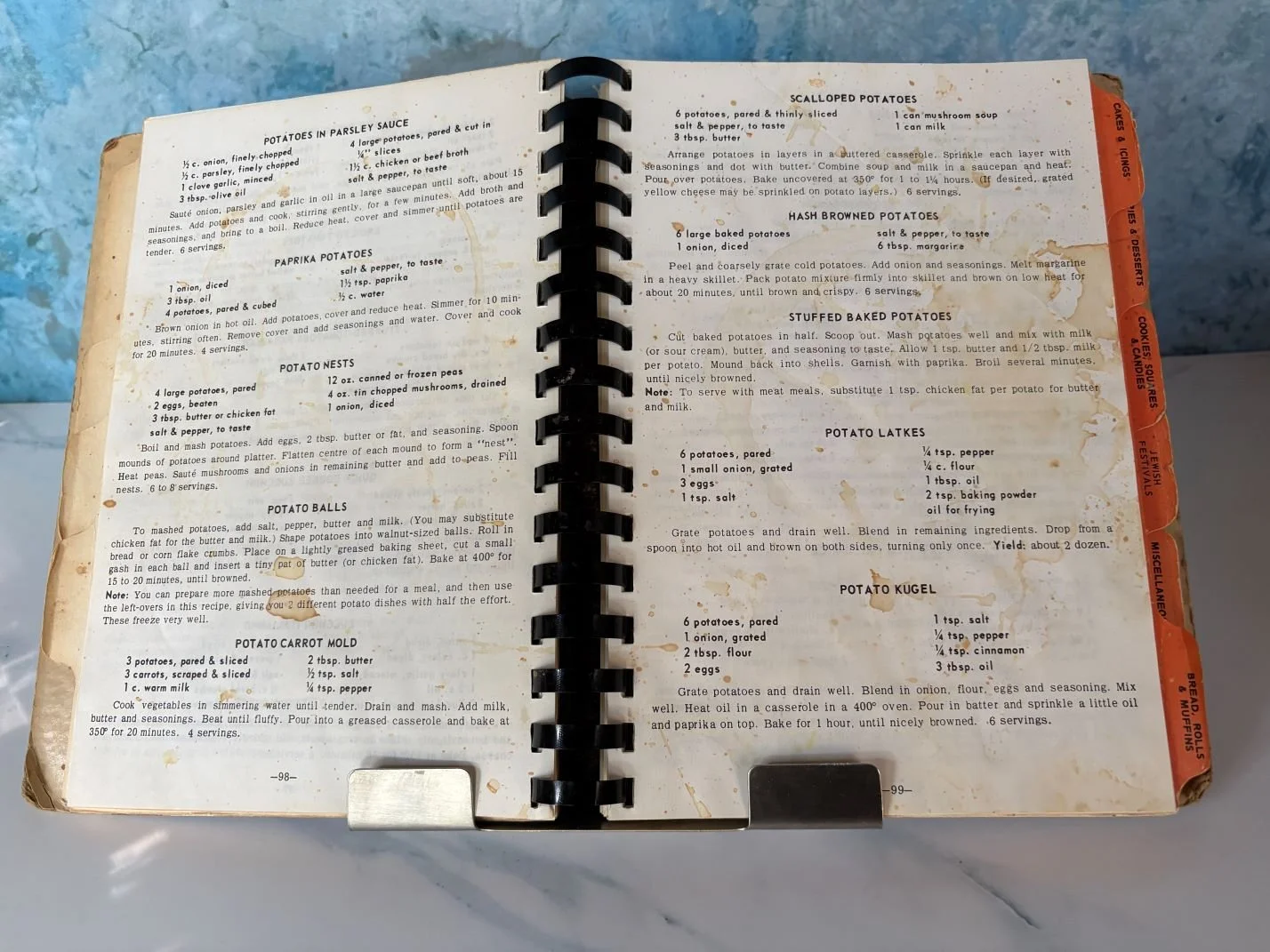

There are also some markings that would have significance to specific people, like if a loved one wrote the note. It could also be food residue from making latkes on a bubby’s recipe, and it just makes you think of her and her delicious latkes whenever you see it.

Is there a point after which markings become significant, or a positive thing in a book? I’m thinking that we would give significance to anything older than 100 years or so, right? Except, perhaps, in the case of a random person marking up what would otherwise be a pristine first edition of a now-famous work?

What is your policy about writing in books?

Hi there! I’m Amélie, a professional home organizer in San Antonio, Texas. I help people like you declutter their home, organize their belongings, and simplify their life. I love cleaning out a closet and removing a carload of donations from a home! My goal is to help you create a functional space that will make your life easier and more peaceful.

Interested? Check out my personalized services or book your complimentary consultation!

Books

A while back, I saw this t-shirt with a dragon that said, “It’s not hoarding if it’s books.” And in that moment, I couldn’t help but agree!

Obviously, there can be such a thing as too many books, but most of the time, people love each one of them so much! The problem is that for many, getting rid of books is heartbreaking, because books are not just paper – they are sentimental objects. The Washington Post had a good article about this recently, with author Fran Lebowitz as one of the subjects – she owns 12,000 books! At that point, I imagine that they would become clutter, in the sense that they would physically be in the way of her living her best life. She can’t bear to part with them, but it’s interesting that she is aware of the issue enough to have designated book heirs in her will.

Our collection of books often represents who we are, or at least who we hope to be, and the fact that we want to expand our mind is a good thing. When author Laura Lippman was faced with this, she had a realization. “Studying my shelves, I realized there were four categories: books I had read and may one day reread, those I had not read but hoped to, those I had read but was never going to reread, and those I was never going to read. The next thing I knew, I had gone into a culling frenzy, pulling almost 100 books in the latter two categories.”

There’s a Japanese term that I want to bring up here: tsundoku. According to that article, “it’s a noun that describes a person who buys books and doesn’t read them, and then lets them pile up on the floor, on shelves, and assorted pieces of furniture.” To me, that is the line in the sand: a tsundoku acquires books almost mindlessly, and perhaps that compulsion could be focused on other objects instead. It’s no longer about the individual books, but about amassing objects without using them. Books are meant to be read!

I advocate mindfulness, in the sense that I recommend you be both aware and honest with yourself. Be aware of how much space your books are taking up versus how much space you would actually rather use for something else. Be honest with yourself about how many books you will have time to read, or whether you really want to indefinitely keep a certain volume that you’ve already read. (The answer can be yes, but not if the whole book collection grows unchecked.)

Marie Kondo says that a book is meant to be read when it comes into your life, so she believes that you should not have a pile of books to read. I must say that this is a point on which I disagree with her! It wouldn’t make sense to go through your pantry or freezer and get rid of everything you don’t plan on eating this very week, right? I feel that it’s the same for books. I love having a small pile of books that I’m looking forward to reading! The trick is simply to keep it manageable. For example, if you read a book a month and have a pile of two dozen books, that means it would take you two years to get through that pile, assuming that you didn’t buy or receive any new books in the meantime (and that’s not exactly a reasonable assumption). You could ask yourself whether each of those books still interests you as much as when you first got it, or if perhaps some of them have been made into movies that you could watch instead. You can also make more time to read.

When it comes to donating books, I find that it’s become harder to do lately. There’s a surprising number of non-profits or charitable organizations that give books or need books, but will only accept brand-new ones, not pre-owned, even if they are in great condition! You could consider sending books to prisoners or troops. You can pass books on to friends who might enjoy them, or sell them at a second-hand bookstore (just make sure you don’t walk out of there with more than you came in!). I also donate books to my local library; some people donate to hospitals, retirement homes, schools, or daycare centers. If you have a Little Free Library near you, that’s a perfect spot as well! As for Laura Lippman, she started a subscription service to mail off her books. “It wasn’t my books that defined me, that shaped the writer I’ve become. It was what was in them—and what is now in me. My memory is a poor one, but I retain from books what I need to retain, usually one perfect image or a dazzling passage. Books deserve to be read, not preserved on shelves where they won’t be cracked open again in one’s lifetime. It’s a mitzvah to pass along titles that I love, a way of playing matchmaker between great writers and avid readers.”